T.J. Clark, The Painting of Modern Life

The shape and pace of production was changing; that much was a commonplace of the time. It was a matter of choice -- or perhaps sometimes of experience -- Whether

Victor-Gabriel Gilbert, Le Carreau des Halles (1880) This is the kind of face-to-face commerce that was being displaced by the department stores |

one stressed in the 1860s the positive or the negative in the new situation: the ruinous effects of the trade treaties and foreign competition, or the marvels in the shopwindows of La Samaritaine; the volume of production, or the shoddiness of the goods; the self-made men, or the bankrupts. Shopwindows, shoddy goods, and bankruptcy: it regularly came down to these. For an ordinarily gloomy businessman in 1870 they were signs of a new order -- the order of the Bon Marché and the Bazar de l'Hôtel de Ville. Genevoix, for instance, knew very well what that system signified:

I know about them, your fashionable shops! Everything done for the sake of display! Ostentation! Instead of high-grade materials, solid and harmonious but costly, your shopwindow will little by little fill up with dubious chiffons-flashy, tasteless, and cheap. Till we arrive at a great music hall of glittering shops, all doing tremendous crooked business, no doubt! ... but with less profits than in districts like ours, and above all less honour !-For after all, it is something to sell merchandise that is good and sound! and to say to oneself each night at bedtime: "I have got richer, and it wasn't to anyone's detriment!"

I may be forced in what follows to water down Genevoix's rhetoric a little, but I want to persuade the reader of its general sense; for it was certainly true that the grands magasins were the signs -- the instruments- of one form of capital's replacing another; and in that they obeyed the general logic of Haussmannization. Were they not built (the voice is approximately Genevoix's again, but it could as well be Lazare's or Gambetta's) with profits derived from the new boulevards and property speculation? Were not the Pereires behind them? Had they not usurped the city's best spaces, lining the Rue de Rivoli, facing the barracks across the Place du Chateau d'Eau and hemming in the Opera? Did they not depend, with windows all hissing with gas till well past nightfall- till ten o'clock in some cases -- on the baron's policemen, his buses and trains, his wide sidewalks, and his passion for "circulation"?

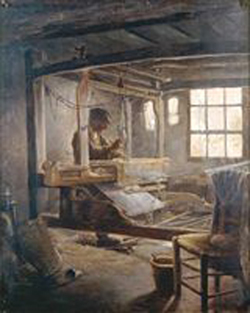

Paul Serusier, The Weaver (1888) Much production in Paris had previously occurred in small shops or apartments, like that of this traditional weaver. |

The stores were everything the opposition came to hate and blame on empire. They were the ruin of the small man. They appeared to grow fat on a diet of merger, speculation, and sudden collapse, and in 1870 it was far from clear that these erratic movements of capital had ceased. (The year before, two of the biggest shops in town, the Diable Boiteux and the Fille Mal Gardee, had combined to form one still larger called La Samaritaine.) The stores were bureaucracies, and the clerks and sales assistants employed in them were no doubt a shiftless and untrustworthy lot: in 1869 they went on strike, demanding a twelve-hour day and holidays on Sundays. Varlin himself exulted at the sight of old divisions ending "which had up to now made workers and shop assistants two different classes." The strike was broken and the counter-jumpers went back to work on worse terms than before, but the very fact of the struggle confirmed the worse fears of honest republicans.

The grands magasins des nouveautes depended, as their name was meant to imply, on buying and selling at speed and in volume. They vied with one another for a multiplicity of lines and "confections"; their shelves were cleared from month to month; they staked everything on fixed prices, low mark-up, and high turnover of stock. They boasted of their ability to mobilize provincial workshops and call on commodities from England, Egypt, or Kashmir. The stores, one might say, put an end to the privacy of consumption: they took the commodity out of the quartier [e.g. neighborhood] and made its purchase a matter of more or less impersonal skill. (No more negotiation face to face, no more pretence of putting one's reputation in jeopardy each time one bought a bolt of worsted or a new frying pan!) The great floors of the Grands Magasins du Louvre were a space any bourgeois could reach and enter, and many did so for fun. They were a kind of open stage on which the shopper strode purposefully and the commodity prompted; they invited the consumer to relish her own expertise and keep it quiet -- not to bargain but to look for bargains, not to have a dress cut out to size but to choose the one which was somehow "just right" from the fifty-four crinolines on show.90

The effect of these shops on the quartier economy was drastic. By the middle of the 1860s much of the pattern of trade in Paris was organized around them. Their agents came into the quarriers with orders written out in hundreds and thousands. They were looking for the kind of goods which it seemed only the artisan workshop could deliver: kitchenware with a hand finish, a well-turned chest of drawers, or the right twist of ribbon on the season's hats. But they made it clear that skill alone would not guarantee the workshop the job. There were ways to economize on skill or do without it, or buy it cheap elsewhere: an agent nowadays could range far afield for the products he wanted, and in particular he could go to the provinces if need be, or to the factories at La Villette. The atelier most often got the contract in the end, but not before the master and men had agreed to work precisely to the agent 's stipulations, however offensive these might be. They had to produce the goods post haste and in quantity. Sometimes the middleman insisted on buying the raw materials himself, and sometimes he set an overall price for the job which forced the workshop to cut costs; in any case, the artisans learnt to use cheaper iron or flimsier paper, and care less for the lasting quality of the result.91 They worked longer hours and

Glove Counter at Au Bon Marche 1889 |

had precious little time to recuperate between jobs: the old regime of breaks and holidays was falling out of favour and the master was more of a stickler for discipline on the workshop floor. The day of rest on saint fundi was fast becoming a sign of recalcitrance or disaffection: to keep it too often was to run the risk of being laid off or sent packing.92

The nature of the job itself was changing. It made no sense in these new conditions -- working against time with shabby materials always deteriorating -- for work to

be shared out in the old way. The tasks were better broken down into separate stages, and each worker was obliged to make one of them his specialty: he learnt and repeated a single pattern of hammer blows on a skillet or a gun barrel, he knew the glues for a certain kind of joint, he handled that stitch, that binding, that type of burnish.93

The master was obliged in times like these to take in work from other shops, and the agent came down with "finishing" work from the suburbs. What that meant for the workman was a few touches of the file on confections ready for sale, but needing the artisan's (forged) signature. The agent proposed new tools and techniques, and pressed for their adoption: he offered to lend money to buy a steam press or a mechanical saw, to introduce standard rivets or convert to chemical dyes. The marchand and the subcontractor arrived with promises of bigger advances and higher profits still, if the workshop would make things faster and more shoddily, and consent to be specialists in a single "line." The outcome of that logic it was one easily reached in the last years of the 1860s-was for the workshop to break up altogether and the agent to deal with a hundred different workers, each with a lathe or a sewing machine at home. That way the agent saved on rent and fuel, and the seamstress was left to bargain direct with capital for her chiffon and cotton reels; in return she was told the agent showed her- what kind of stitching was all the rage that winter, what shape of bustle, what length of hem.